Beirut, Lebanon – For the past two months, St Francis Church in Hamra has taken in displaced families from southern Lebanon and Dahiyeh, a constellation of Beirut suburbs.

It’s been a difficult time for many of the families who fled Israeli bombing and a ground offensive in the south, but since early Wednesday when a ceasefire came into effect, there has been a different energy in the air.

Standing by the door to the church’s car park, where the displaced have pitched tents, Ibrahim Termos, 25, radiated joy when asked about the ceasefire on Wednesday.

Around him, people were packing up their tents and belongings as they prepared for the journey back home.

“It’s not about just a ceasefire but that we won a ceasefire,” Termos said, smiling. He lost his home in this war, but the fact the nightmare of the past two months is over has him focusing on the positive.

“Our apartment was destroyed, but the building is still standing,” Termos said.

A celebratory mood

After nearly 14 months of fighting, the Lebanese armed group Hezbollah and Israel agreed to a ceasefire.

It stipulates that Israel must withdraw from Lebanon, and Hezbollah is to retreat north of the Litani River. The Lebanese military is to deploy to fill that space along the border with Israel within 60 days.

While some people were sceptical that Israel would commit fully to the ceasefire – doubts that resurfaced on Thursday as Israel fired on a number of locations in Lebanon – the general mood was euphoric.

A quarter of Lebanon’s population has been displaced in the war, and videos and photos of packed roads circulated on social media as people headed home before the day even broke on Wednesday.

Beirut was in a celebratory mood that morning as cars piled high with mattresses and other belongings departed from hotels and shelters.

Posters of the late Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah adorned many cars, and some waved Hezbollah flags from their windows.

Some images also featured the late Hachem Safieddine, who was thought to be Nasrallah’s likely successor before his assassination a few days after Nasrallah’s.

Women wave Hezbollah flags as they drive past a damaged building at the entrance of Dahiyeh [Mohamed Azakir/Reuters]

In Zkak el-Blat, a convoy of motorcycles waving the red and green flags of Harakat Amal, the party of Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri, who negotiated the ceasefire on behalf of Hezbollah, sped down a street, honking in celebration.

‘I hope …’

At St Francis Church, many of the displaced who had homes to return to left early in the morning.

Some whose houses are in the deep south in places like Khiam where the devastation was brutal and Israeli soldiers may still be present said they would stay another day.

The people in the shelter have lived through some hard moments, but many are optimistic that this fragile peace will hold and the country will prosper once more.

“I hope we have a beautiful future with no violence,” Mohsen Sleiman, 48, said. “And that in our kids’ futures, they don’t see war and destruction.”

Despite losing his home in Dahiyeh and his home in his village of al-Bayyaada in southern Lebanon, Sleiman is defiant, stressing that the most important thing is his family’s safety.

“We’re used to this,” he said. “It’s a victory for all of Lebanon, not just a single sect.”

Hussein Ismail, 38, was standing nearby, watching his young son bounce a football in his hands.

Born during the Lebanese Civil War, he has been through the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel as well.

Throwing his hands up, he exclaimed: “We’ve lived in this kind of environment since our childhood.

“Now, we want to live independently.”

“I’ll go home, God willing,” he said. “I don’t know if my home in Choueifat [a neighbourhood in Dahiyeh] is still standing, but everything will be OK.”

Father Abdallah, wearing a brown robe and glasses, is speaking with displaced people who are packing up and preparing to go home.

“I’m happy people get to go home,” he said.

“There’s joy and feelings of victory. They’re all happy. They see that there’s beauty in what’s ahead.”

His Roman Catholic church, Abdallah said, opened its doors to everyone in need, regardless of sect or religion.

“We welcomed them. In the end, the important thing is the dignity of life. Dignity is a minimum.”

Many in Lebanon doubted a ceasefire would ever work, but once it took effect, the outpouring of joy was ubiquitous.

For his part, Abdallah spoke with cautious optimism.

“Personally, I say, God willing, it holds,” he said. “It depends, but the hope is it holds 100 percent.”

A fragile peace but likely to persist

As the day wore on, reports came in of Israeli violence as its soldiers wounded two journalists in Khiam and fired at cars. But the ceasefire nonetheless appeared to hold.

For now, breaking the ceasefire would be highly unfavourable for either side as the political and military consequences would outweigh any potential gains.

At a bookshop in Hamra, grey-haired intellectuals sat among piles of books, discussing the latest developments.

Sleiman Bakhti read the ceasefire’s conditions closely [Raghed Waked/Al Jazeera]

“The whole issue was never about Lebanon,” said Sleiman Bakhti, the shop’s owner. “The negotiations [with Israel] should have been directly with [Hezbollah’s main backers] Iran.”

Bakhti believes a new chapter is emerging for Lebanon, one that is less defined by Iran and more by Israel and its allies – and the ceasefire may be the first paragraph in that new chapter.

Also sitting in the bookshop is longtime radio correspondent Bassem Elmoualem, an expert on the United States and Central America.

While many were looking at the short-term implications of the ceasefire, Elmoualem’s decades as a political observer have taught him to look at the bigger picture.

Israel’s actions, he said, led to the collapse of its global image.

“October 7 [2003] was the beginning of the end,” he said. “[Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu is dead.”

Cars drive past the rubble of damaged buildings in Dahiyeh [Mohamed Azakir/Reuters]

Related News

Israel ramps up attacks on Lebanon as officials study US ceasefire plan

Europe braces for a ‘swift and brutal transition’ to the world of Trump

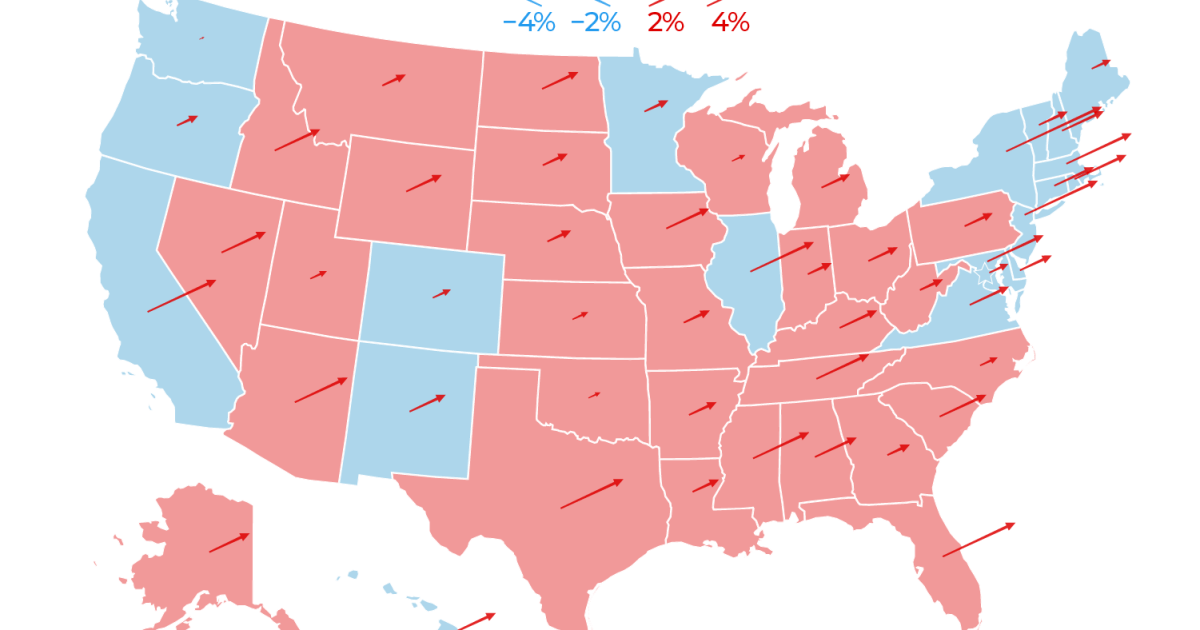

US election results map 2024: How does it compare to 2020?