As United States naval deployments in the Caribbean intensify and rhetoric heats up, the prospect of a US attack on Venezuela feels increasingly close.

Since early September, the US has carried out military strikes on at least 21 Venezuelan boats it claims are trafficking drugs in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific, killing at least 87 people. The Trump administration has justified the attacks as, it says, the inflow of drugs to the US threatens national security. However, it has provided no evidence of drug trafficking, and experts say Venezuela is not the main source of drugs such as cocaine being smuggled into the US.

US President Donald Trump has given conflicting messages about whether he plans a ground operation inside Venezuela. He has simultaneously not ruled it out, while also denying he was considering strikes inside the country. He has, however, authorised CIA operations inside the country.

Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro claims Trump’s real objective is to force a regime change by removing him from power, and warned that the country would resist any such attempt.

Here is what we know:

How could the US attack Venezuela?

Analysts say the US has several military options for striking Venezuela, most of which employ air and maritime power rather than ground troops.

In recent months, the US has deployed a considerable air and naval force to the Caribbean, close to the coast of Venezuela, including the world’s largest aircraft carrier, the USS Gerald Ford.

“The pieces are in place for an air and missile attack,” Mark Cancian, a retired Marine Corps colonel and senior adviser with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told Al Jazeera.

Advertisement

“The first strike will likely be long-range missiles launched from air and sea because Venezuela has relatively strong air defences,” he said.

While the Trump administration’s rhetoric has increasingly focused on the Maduro government, which it claims has links to drug gangs in Venezuela, analysts note that targeting alleged cartel-linked infrastructure would be easier to justify internationally and easier to conclude quickly.

What nearly all experts have ruled out is a ground invasion.

“I don’t really see that an attack is likely at all at this stage,” Elias Ferrer, founder of Orinoco Research and the lead editor of the Venezuelan media organisation Guacamaya, said.

“There will be no boots on the ground because US ground forces in the region are not strong enough for an invasion,” Cancian said.

Furthermore, a large-scale land operation would likely be deeply unpopular in the US and face major obstacles at home.

“Any move toward overt ground operations would encounter significant legal barriers, congressional pushback, and the shadow of Iraq and Afghanistan – all of which make a full occupation extremely unlikely,” Salvador Santino Regilme, a political scientist who leads the international relations programme at Leiden University in the Netherlands, told Al Jazeera.

“Analytically, we should think in terms of a spectrum of limited but potentially escalating uses of force, not a binary choice between ‘no attack’ and an Iraq-style invasion,” he added.

An ‘Iraq-style invasion’ refers to a large-scale ground campaign followed by a US-led occupation, the dismantling of state institutions and an open-ended nation-building effort – the kind of intervention that would require hundreds of thousands of troops, years of counterinsurgency operations, and massive political and financial investment.

What could a US attack mean for Venezuela?

While some policymakers in Washington hope a military strike would trigger a political transition in government, analysts warn it is far more likely to plunge the nation into instability.

Ferrer described the idea of an attack as opening a “Pandora’s box”.

“Armed actors are empowered in a conflict, so either the military itself or paramilitary actors – whether they’re politically motivated or just organised crime – could try to take over certain parts of the country. That is not the only result. But you open up all of those possibilities.”

Advertisement

In such an environment, Ferrer warned, the political opposition would be among the least likely to benefit.

“One of the most likely losers out of such a situation is the Venezuelan opposition, only because they don’t have an armed wing or strong connections with the armed and security forces,” he said.

Indeed, some analysts argue that even a limited US strike would likely strengthen the Maduro government in the short term.

“External aggression tends to generate a rally-around-the-flag effect and gives incumbents a powerful pretext to criminalise dissent as treason,” Santino Regilme told Al Jazeera.

“The opposition, which is already fragmented and socially uneven, would likely be further divided between those who welcome US pressure and those who fear being permanently discredited as foreign proxies,” he added.

“Comparative experiences in Iraq, Libya, and other cases of externally driven regime change suggest that coercive intervention rarely produces stable democracy,” Santino Regilme explained.

Despite rising tensions, senior Venezuelan officials have adopted an openly defiant posture. While publicly calling for peace, they frame any potential US action as an attack on national sovereignty.

“They [the US] think that with a bombing they’ll end everything. Here, in this country?” Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello scoffed on state television in early November.

Maduro struck a similar tone earlier this month.

“We want peace, but peace with sovereignty, equality and freedom,” he said. “We do not want a slave’s peace, nor the peace of colonies.”

What is the US’s main strategy?

Cancian, the retired Marine Corps colonel from CSIS, said the US, through the CIA, is working to undermine the loyalty of the Venezuelan military to the Maduro government.

“The United States may tell these forces that they will be left alone if they remain in garrison during any fighting,” Cancian explained.

“The US did something like this during Desert Storm,” he said. That was the 1991 Gulf War campaign in which a US-led coalition expelled Iraqi forces from Kuwait.

In that conflict, US officials quietly signalled to certain Iraqi units that if they stayed in their barracks and did not resist, they would not be targeted – an approach that helped limit resistance during the ground offensive.

But, according to Cancian, the Venezuelan government has purged any opposition from the military.

“Thus, there is a high likelihood that the military and security forces will fight,” he added

So how could Venezuela’s military respond to an attack?

Ferrer said this all depends on what signals the US sends them before any attack. “What’s actually more interesting is what kind of deal the US is trying to make. How is it trying to involve or marginalise the armed forces and the security forces?”

He outlined the dilemma facing Washington: “Is it telling them, ‘Hey guys, you can stay in control of these businesses, these ministries – the generals can keep their posts’? Or is it going to do something like de-Baathification in Iraq, where they remove all the officers and fire all the soldiers to purge the armed forces of pro-Maduro elements?”

Advertisement

Marginalising the armed forces could trigger more, not less, violence, Ferrer warned.

“Not necessarily a coup or a civil war involving the whole country, but you might have pockets of conflict arising all over the country. That’s definitely a possibility if the armed forces are marginalised,” he added.

How might ordinary Venezuelans react?

Analysts say the picture is complex. “Ordinary Venezuelans have already endured a prolonged socioeconomic collapse, hyperinflation, widespread shortages, international sanctions and one of the largest displacement crises in the world,” Santino Regilme said.

According to recent estimates, about 7.9 million Venezuelans, roughly 28-30 percent of the population, have required humanitarian assistance in 2025.

“Against that backdrop, a US attack would likely be experienced less as a moment of ‘liberation’ and more as yet another layer of insecurity, one that threatens what remains of access to food, medicine, electricity and basic services.”

“Public opinion research shows deep distrust both toward the government and toward foreign military intervention, suggesting that popular reactions would be heterogeneous, ambivalent, and heavily shaped by class, geography, and political identity,” Santino Regilme added.

How would Venezuela’s international partners respond?

Regional and global actors would likely react in ways that mirror their existing strategic ties with Caracas.

According to analysts, China, now one of Venezuela’s largest creditors and economic partners, is expected to maintain firm diplomatic support for Maduro, but its ability to shape events on the ground would be limited if open conflict erupted.

“In the event of an armed conflict developing between Venezuela and the US, we understand that China’s capacity for influence would be reduced,” Carlos Pina, a Venezuelan political analyst, told Al Jazeera.

Russia, by contrast, has a more direct military relationship with Venezuela. Moscow has supplied advanced weapons systems, trained Venezuelan personnel, and maintained intelligence cooperation for years.

According to Pina: “Moscow’s [role] would be linked to possible military advisory regarding the use of military equipment that this Eurasian country has sold to Caracas.”

In any scenario, both countries would remain politically aligned with Maduro. As the expert noted, “the diplomatic support of these countries for Nicolas Maduro would be undisputed.”

Could the US target other countries?

Analysts caution that US aggression towards Venezuela could have regional implications.

During a cabinet meeting on Tuesday this week, Trump warned that any country producing narcotics would be a potential target, and singled out Colombia for producing cocaine, which ends up in the US.

Experts say they fear that what is unfolding now with Venezuela, therefore, could become a broader template for reframing domestic political crises across the region as “narco-terrorist” threats – a label that can justify military action under the banners of counterterrorism or law enforcement.

Santino Regilme told Al Jazeera that “what is being tested around Venezuela is less a single country policy than a broader template, where complex domestic crises are reframed as ‘narco-terrorist’ threats that justify extraterritorial use of force under the banners of law enforcement and counterterrorism”.

Advertisement

If applied to other countries in the region, he warned, this model could “further erode the already fragile constraints on the use of force in international law and weaken regional mechanisms that seek negotiated political settlements”.

Santino Regilme added that such an approach would also deepen the trend towards managing transnational issues – like drug trafficking and migration – through militarisation rather than social, economic or public health interventions.

Related News

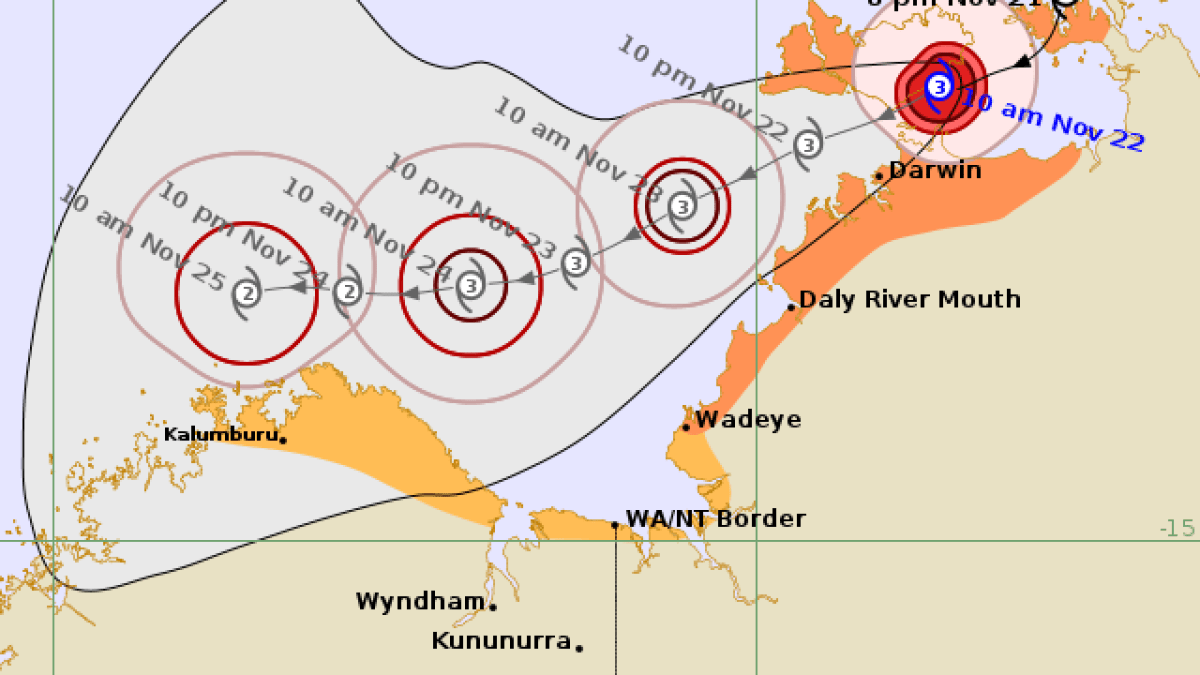

Australia’s Northern Territory braces for Tropical Cyclone Fina

Former President Jair Bolsonaro asks to serve house arrest in Brazil

Why has Venezuela banned six international airlines amid US tensions?